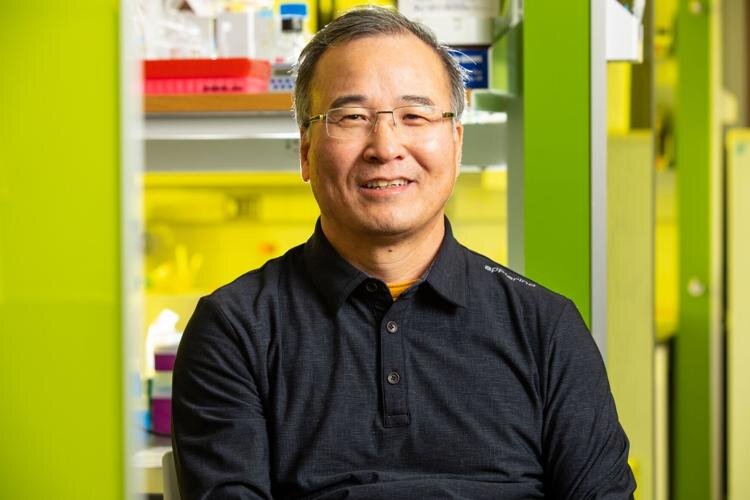

Soo-Kyung Lee, Empire Innovation Professor of Biology at the University at Buffalo, has been driven to focus greater attention on FOXG1 syndrome since her daughter, Yuna, was diagnosed with the neurological condition almost nine years ago.

Douglas Levere/University at Buffalo

Maybe Yuna Lee was built to be in Buffalo.

The 11-year-old – whose name means “snow girl” in a Korean dialect – was born during a rare January snowstorm in Houston, where her parents worked as medical researchers at Baylor College of Medicine.

Yuna seemed a typical newborn, but things changed in months that followed. Her head didn’t grow quickly enough. Seizures became common. She missed developmental milestones.

It took two years for doctors and top U.S. neurologists to tease out a diagnosis, which at first seemed unfathomable to her mother, Soo-Kyung Lee, a leading researcher in genetic brain disorders.

Yuna had FOXG1 syndrome, a rare condition caused by a random mutation in a key gene needed during fetal development to set the stage for speech, mobility and thought.

“Yuna was born in the right place, to the right mom. She kind of came to the right family,” said Jae Lee, her father, who for most of his career focused on diabetes and metabolic research.

The Lee parents, both biology professors, spent the bulk of the last decade at Oregon Health and Science University, on the West Coast in Portland, slowly taking more professional time on their daughter’s condition – until they were drawn in summer 2019 to the University at Buffalo by the prospect of creating a center of excellence in FOXG1 research.

Jae Lee, above, and his wife, Soo-Kyung Lee, natives of South Korea, came to Buffalo from Portland, Oregon two years ago with aims to create a center of excellence in FOXG1 research.

Douglas Levere/University at Buffalo

Their lab on the UB North Campus already has yielded greater understanding about how the related syndrome develops, raising hopes that their work could one day help with breakthrough research and treatment, including for related conditions such as autism, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy and schizophrenia.

Much work remains, Soo-Kyung Lee said.

The FOXG1 gene, once called “Brain Factor 1,” is a master regulator that is key to establishing cells that build the central nervous system, particularly the forebrain.

Yuna lacked a nucleotide, Number 256 in the 86th amino acid of one of two copies of FOXG1, which has 489 amino acids. Those born with such mutations on both copies cannot survive.

This and similar mutations almost always happen randomly, as was the case with Yuna.

Her mother has long used genes in the FOX family, including FOXG1, in her research.

Roughly 400,000 babies born worldwide have neurological disorders caused by random mutations.

Dr. Joseph Gleeson, a neurogeneticist at University of California San Diego, told the New York Times for a 2018 story on the Lees that doctors used to lump all those conditions together under autism or other categories before genetic sequencing became more common and provided more clarity.

“It’s really changing the way doctors are thinking about disease,” Gleeson told the Times.

Only about 650 people in the world are known to have FOXG1 syndrome, although FOXG1 genes also play a role in several other neurological conditions.

An estimated one in 68 children is diagnosed on the autism spectrum. More than 44 million people have Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia worldwide. More than 2 million Americans have epilepsy. Roughly the same number have schizophrenia.

Yuna cannot talk, walk or eat on her own. She lacks control of her bowels. For years, she found it hard to sleep. She has learned to sit up and is making other slow, steady progress with help from physical, occupational and speech therapy. She communicates basic needs with her eyes and other facial expressions. She and her family live in Amherst.

She and her brother, Joon, 8, attended Maple East Elementary School before the pandemic, but have been learning at home because of coronavirus risks for Yuna. An experienced caregiver looks after the children while the Lees work mostly from home.

“It's not ideal,” Jae Lee said. “We look forward to the day that we can send Yuna back to school and back to the clinics, but we've been coping as well as we could have under the circumstances.”

Meanwhile, related research progresses. Those financially supporting the work of the Lees include New York State, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the FOXG1 Research Foundation.

FOXG1 research could have implications for several neurological diseases, said Soo-Kyung Lee, including autism, Alzheimer’s, epilepsy, and schizophrenia.

Douglas Levere/University at Buffalo